Front cover:

Date proof: https://web.archive.org/web/20100910123 ... ree-right-

Original link:

https://web.archive.org/web/20101005142 ... ng-midwest

It can also be previewed here: https://issuu.com/xlr8r/docs/xlr8r_135

And downloaded here: https://web.archive.org/web/20111224181 ... 8R_135.pdf

Print version:

Click to view

Click to read

Midnight Mass: The bewitching Midwest trio Salem ponders Juggalos, cultural authenticity, and not giving a fuck.

Words: Brandon Ivers

Photo: Shawn Brackbill

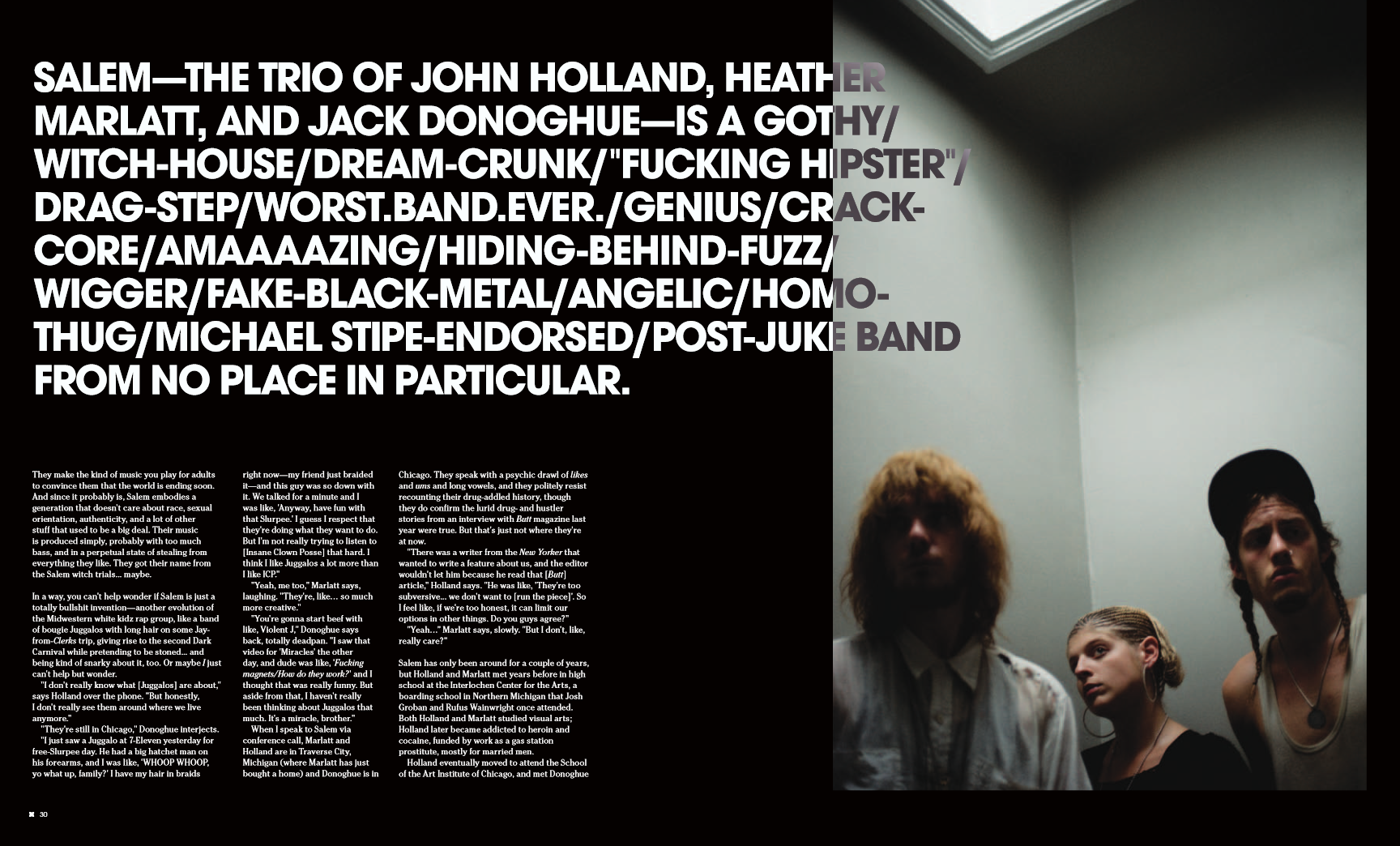

Salem—the trio of John Holland, Heather Marlatt, and Jack Donoghue—is a gothy/witch-house/dream-crunk/"fucking hipster"/drag-step/worst.band.ever./genius/crack-core/amaaaazing/hiding-behind-fuzz/wigger/fake-black-metal/angelic/homo-thug/Michael Stipe-endorsed/post-juke band from no place in particular.

They make the kind of music you play for adults to convince them that the world is ending soon. And since it probably is, Salem embodies a generation that doesn't care about race, sexual orientation, authenticity, and a lot of other stuff that used to be a big deal. Their music is produced simply, probably with too much bass, and in a perpetual state of stealing from everything they like. They got their name from the Salem witch trials... maybe.

In a way, you can't help wonder if Salem is just a totally bullshit invention—another evolution of the Midwestern white kidz rap group, like a band of bougie Juggalos with long hair on some Jay-from-Clerks trip, giving rise to the second Dark Carnival while pretending to be stoned... and being kind of snarky about it, too. Or maybe I just can't help but wonder.

"I don't really know what [Juggalos] are about," says Holland over the phone. "But honestly, I don't really see them around where we live anymore."

"They're still in Chicago," Donoghue interjects.

"I just saw a Juggalo at 7-Eleven yesterday for free-Slurpee day. He had a big hatchet man on his forearms, and I was like, 'WHOOP WHOOP, yo what up, family?' I have my hair in braids right now—my friend just braided it—and this guy was so down with it. We talked for a minute and I was like, 'Anyway, have fun with that Slurpee.' I guess I respect that they're doing what they want to do. But I'm not really trying to listen to [Insane Clown Posse] that hard. I think I like Juggalos a lot more than I like ICP."

"Yeah, me too," Marlatt says, laughing. "They're, like… so much more creative."

"You're gonna start beef with like, Violent J," Donoghue says back, totally deadpan. "I saw that video for 'Miracles' the other day, and dude was like, 'Fucking magnets/How do they work?' and I thought that was really funny. But aside from that, I haven't really been thinking about Juggalos that much. It's a miracle, brother."

When I speak to Salem via conference call, Marlatt and Holland are in Traverse City, Michigan (where Marlatt has just bought a home) and Donoghue is in Chicago. They speak with a psychic drawl of likes and ums and long vowels, and they politely resist recounting their drug-addled history, though they do confirm the lurid drug- and hustler stories from an interview with Butt magazine last year were true. But that's just not where they're at now.

"There was a writer from the New Yorker that wanted to write a feature about us, and the editor wouldn't let him because he read that [Butt] article," Holland says. "He was like, 'They're too subversive... we don't want to [run the piece]'. So I feel like, if we're too honest, it can limit our options in other things. Do you guys agree?"

"Yeah…" Marlatt says, slowly. "But I don't, like, really care?"

Salem has only been around for a couple of years, but Holland and Marlatt met years before in high school at the Interlochen Center for the Arts, a boarding school in Northern Michigan that Josh Groban and Rufus Wainwright once attended. Both Holland and Marlatt studied visual arts; Holland later became addicted to heroin and cocaine, funded by work as a gas station prostitute, mostly for married men.

Holland eventually moved to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and met Donoghue while working at American Apparel. Upon their first meeting, Donoghue outlined his terms of friendship by asking Holland to "disconnect" from his other friends, to which Holland agreed, half-earnestly. In the Butt interview, Holland described Donoghue as "the hottest person I've ever met."

Marlatt met Donoghue while visiting Holland in Chicago for the summer, and the three immediately clicked. Donoghue and Holland had been working on high(er)-energy dance music, but Marlatt's presence shifted the focus to Salem. "We just had a certain understanding about things," says Holland. "We understand without having to talk about it."

The group's first full-length, King Night, comes out in late September on IAMSOUND Records, and it'll probably be the grandest moment of the so-called "witch house" scene's non-existence. The opening title track is a teeth-grinding Christmas anthem perverted by fanatical choir stabs and crumbling, blown-out subs. It's basically Salem's annihilation hymn, and it puts their most fierce, polarizing foot forward.

The band's previous releases over the last two years (like the Yes I Smoke Crack and Water EPs, and the "Frost" b/w "Legend" single) offered a good hint of what Salem was capable of, but they were like partially finished ideas. King Night is far more realized in comparison, taking tracks from old releases ("Redlights," "Frost," and the YouTube-leaked "Trapdoor") and re-mastering them with Brooklyn producer Dave Sardy. The end result isn't necessarily what you'd call slick or accessible, but, along with eight new tracks on the album, Salem's towering, overblown aspirations finally begin to make sense.

The songs on King Night tend to intersect around a few main components: a weird, percussive mix between Chicago juke and southern rap, a blissed-out wash of synths and vocals reminiscent of Cocteau Twins, and a fast-and-slow polyrhythm of fanned-out hi-hats and crisis sounds. There's other shit thrown in there for good measure, too—the gabber kick-drum squash on "Asia," or the almost-dubstep bass pressure on "Tair"—but pinpointing all those parts implies a reverence for influence that Salem doesn't really bother with. "We're taking liberally from so much," says Donoghue. "We're taking from rock, drone, European rave music, southern rap, Chicago, New York, whatever."

When I mention specific artists like Chicago juke/footwork producer DJ Nate, Donoghue says he's never met the early-20-something beatmaker, but he's definitely a fan. "His music is so smart," he says, "but I don't think he's, like, trying to be clever." Other guys like Gucci Mane (of whom Salem has done several unofficial remixes) and Wacka Flocka Flame are held in similarly high regard, but it's more like a detached appreciation than anything resembling gushing. "We don't really know that much about any one kind of music," says Holland. "We like so many different kinds of music, but we don't do too much background research. We're just trying to find individual songs that we like."

"We all focus on different things, too," Donoghue adds. "Like, I know Heather really likes music that has bells in it—more than I do—and I like certain rap that John and Heather can appreciate, but maybe not listen to it as much. John has a whole bunch of other shit that I don't even know about at all. But we share a lot of music with each other and we share a lot of ideas—verbal and conceptual. Salem is where all our aesthetics meet."

The band works on songs collectively, but each member has a specific identity within each track. On "Trapdoor," Donoghue raps in a pitched-down, incomprehensible growl, and his hook, "It's all blurred out/Hey bitch, I can't see ya" could almost be mistaken for Gucci Mane. On "Traxx," Marlatt's singing is pure texture amidst a haze of deathray synths, bass, and prison clanks. And Holland sings as well. On "Killer," he conjures up a strange, rap-laced industrial rock combination that borders on pure noise.

Salem's influences might seem a little iPod-playlist-driven, but in an era of Rick Ross studio gangsterism and rock 'n' roll dudes coming out with macrobiotic cookbooks, it's hard to harp too hard on authenticity. That said, if M.I.A. can be burned at the stake for eating truffle fries, what does it mean when white kids with art-school credentials start pitching their voices down to sound like Gucci Mane?

"No one would ever question us for, like, reversing a guitar or something," says Donoghue. "And, like, with juke, I'm from Chicago. I grew up in Chicago."

"And I lived there for five years," adds Holland.

"I feel like that's something a white person would say," says Marlatt. "In a way to criticize what we're doing. It's like, to anyone that thinks that in this era—I don't know what to tell them. It's not like we're Elvis Presley. God. What, are we robbing the music from a different race? Give me a break."

"There's no such thing as owning anything in music or art or anything like that," says Holland.

"Yeah, like, I've found music that has been remade from chopped-up parts of beats that I did in high school," says Donoghue. "But I'm happy [someone] took the song in a different direction. It's not anyone's song."

That's the sort of controversy that surrounds Salem these days. That, and grumblings about their live shows, the most ballyhooed of which was at the SXSW FADER Fort earlier this year. According to those who were there, including The FADER magazine's own Matthew Schnipper, the show fell somewhere between brilliantly not good and just not good—they may or may not have been booed off stage, it's hard to tell. At any rate, videos from the performance remain on YouTube.

When I ask Salem about SXSW and the FADER Fort videos, there's a moment of sincere confusion.

"I never, like, saw the video, so I don't know," says Marlatt.

"Was that, like, a YouTube video?" asks Donoghue. "I don't get it."

"Yeah, it's on YouTube," I say. "I guess the video was taken offline for a second or something?"

"That was only, like, our eighth show," Holland says after a long pause.

"There's a lot of people that want to weigh in on our live show and how it is and how it should be," Donoghue says, almost laughing. "I'm just like, straight up, I would never talk to you. I wouldn't talk to you about what I want my music to sound like, I wouldn't talk to you about what I wanted my art to look like, or like, hang out with you. So why do you think you should be weighing in on things?"

"I wanna be like, 'Why didn't you ask someone else to do it then?'" says Marlatt. "People were saying stuff like, 'Other bands would die to have the opportunities that you guys have, to get the shows that you get.' Like, [these bands] trying for years, and then they finally get to play [the FADER Fort]. And I don't even know what to say when people say stuff like that. It's like, 'Okay, well… sorry?'"

"The only reason we started doing shows was because someone offered to fly us to Rome to play," admits Donoghue. "So we were like, 'Okay, that would be fun,' you know what I'm saying? We're still trying to figure it out, and we will figure it out, but live performance isn't really—we don't have that much experience with it. We're still trying to come to a place where it's as moving as the actual music we make. These shows were part of our exploration phase. We're playing bigger venues than maybe we're prepared for."

The problem is, people still really want to see Salem—at least people like music journalists, Terence Koh, and Michael Stipe—all of whom showed up to what was probably Salem's third or fourth show at Brooklyn's Glasslands Gallery in January. How do you keep such heavy-hitters away while Salem slowly, painfully perfects its live show?

"I don't even care. I totally don't," says Marlatt. "I'm totally confused by that whole world. I think we're more concerned with doing performance-based things, rather than standing around... just playing music. We want to do way more than that. But up until this point we haven't had any of the resources to really do what we have in our heads. But now we kind of do, and that's exciting."

As the interview continues, there's a loud noise that keeps barging its way into the phone call—either a large barking dog or maybe a boar—and I'm reminded that Holland and Marlatt are set up in Northern Michigan—home of Midwestern desolation, pain and suffering, upside-down crosses stuck in the snow, etc. But I'm also struck by how laid-back and sort of positive everyone seems to be.

"I feel like people imagine us as being so serious or dark or whatever," says Marlatt, "but it's not really like that. We don't take ourselves seriously, but we take our music very seriously. It's not about each of us as individuals. Like, 'Oh, Jack went to a party last night.' Who cares? It has nothing to do with our music."

Prior to talking with Salem, it all seemed so obvious: Teams of marketing men carefully cultivated this band's persona using magnets and only the best SEO-baiting tricks—some real buzzband conspiracy shit! But it turns out the reality is much more banal. Their music—and their aesthetic aura—is ambiguous and full of fuzzy definitions, but Salem is not part of a JT LeRoy-style hoax; the darkness and the crack smoking and whatever else come from a more intuitive lack of giving a shit than some secret, unfolding plan.

"I think you're giving us more credit for thinking about our 'audience' than we actually do," Donoghue eventually admits. "We're not even trying to be secretive or sensational. It's just that we're not thinking about people passing judgments. We're making what we want to be listening to. It's not like we're making anything just to get a reaction from people. If we just wanted to be sensational or whatever, we have a lot more stories we could have told."

King Night is out September 28 on IAMSOUND

Words: Brandon Ivers

Photo: Shawn Brackbill

Salem—the trio of John Holland, Heather Marlatt, and Jack Donoghue—is a gothy/witch-house/dream-crunk/"fucking hipster"/drag-step/worst.band.ever./genius/crack-core/amaaaazing/hiding-behind-fuzz/wigger/fake-black-metal/angelic/homo-thug/Michael Stipe-endorsed/post-juke band from no place in particular.

They make the kind of music you play for adults to convince them that the world is ending soon. And since it probably is, Salem embodies a generation that doesn't care about race, sexual orientation, authenticity, and a lot of other stuff that used to be a big deal. Their music is produced simply, probably with too much bass, and in a perpetual state of stealing from everything they like. They got their name from the Salem witch trials... maybe.

In a way, you can't help wonder if Salem is just a totally bullshit invention—another evolution of the Midwestern white kidz rap group, like a band of bougie Juggalos with long hair on some Jay-from-Clerks trip, giving rise to the second Dark Carnival while pretending to be stoned... and being kind of snarky about it, too. Or maybe I just can't help but wonder.

"I don't really know what [Juggalos] are about," says Holland over the phone. "But honestly, I don't really see them around where we live anymore."

"They're still in Chicago," Donoghue interjects.

"I just saw a Juggalo at 7-Eleven yesterday for free-Slurpee day. He had a big hatchet man on his forearms, and I was like, 'WHOOP WHOOP, yo what up, family?' I have my hair in braids right now—my friend just braided it—and this guy was so down with it. We talked for a minute and I was like, 'Anyway, have fun with that Slurpee.' I guess I respect that they're doing what they want to do. But I'm not really trying to listen to [Insane Clown Posse] that hard. I think I like Juggalos a lot more than I like ICP."

"Yeah, me too," Marlatt says, laughing. "They're, like… so much more creative."

"You're gonna start beef with like, Violent J," Donoghue says back, totally deadpan. "I saw that video for 'Miracles' the other day, and dude was like, 'Fucking magnets/How do they work?' and I thought that was really funny. But aside from that, I haven't really been thinking about Juggalos that much. It's a miracle, brother."

When I speak to Salem via conference call, Marlatt and Holland are in Traverse City, Michigan (where Marlatt has just bought a home) and Donoghue is in Chicago. They speak with a psychic drawl of likes and ums and long vowels, and they politely resist recounting their drug-addled history, though they do confirm the lurid drug- and hustler stories from an interview with Butt magazine last year were true. But that's just not where they're at now.

"There was a writer from the New Yorker that wanted to write a feature about us, and the editor wouldn't let him because he read that [Butt] article," Holland says. "He was like, 'They're too subversive... we don't want to [run the piece]'. So I feel like, if we're too honest, it can limit our options in other things. Do you guys agree?"

"Yeah…" Marlatt says, slowly. "But I don't, like, really care?"

Salem has only been around for a couple of years, but Holland and Marlatt met years before in high school at the Interlochen Center for the Arts, a boarding school in Northern Michigan that Josh Groban and Rufus Wainwright once attended. Both Holland and Marlatt studied visual arts; Holland later became addicted to heroin and cocaine, funded by work as a gas station prostitute, mostly for married men.

Holland eventually moved to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and met Donoghue while working at American Apparel. Upon their first meeting, Donoghue outlined his terms of friendship by asking Holland to "disconnect" from his other friends, to which Holland agreed, half-earnestly. In the Butt interview, Holland described Donoghue as "the hottest person I've ever met."

Marlatt met Donoghue while visiting Holland in Chicago for the summer, and the three immediately clicked. Donoghue and Holland had been working on high(er)-energy dance music, but Marlatt's presence shifted the focus to Salem. "We just had a certain understanding about things," says Holland. "We understand without having to talk about it."

The group's first full-length, King Night, comes out in late September on IAMSOUND Records, and it'll probably be the grandest moment of the so-called "witch house" scene's non-existence. The opening title track is a teeth-grinding Christmas anthem perverted by fanatical choir stabs and crumbling, blown-out subs. It's basically Salem's annihilation hymn, and it puts their most fierce, polarizing foot forward.

The band's previous releases over the last two years (like the Yes I Smoke Crack and Water EPs, and the "Frost" b/w "Legend" single) offered a good hint of what Salem was capable of, but they were like partially finished ideas. King Night is far more realized in comparison, taking tracks from old releases ("Redlights," "Frost," and the YouTube-leaked "Trapdoor") and re-mastering them with Brooklyn producer Dave Sardy. The end result isn't necessarily what you'd call slick or accessible, but, along with eight new tracks on the album, Salem's towering, overblown aspirations finally begin to make sense.

The songs on King Night tend to intersect around a few main components: a weird, percussive mix between Chicago juke and southern rap, a blissed-out wash of synths and vocals reminiscent of Cocteau Twins, and a fast-and-slow polyrhythm of fanned-out hi-hats and crisis sounds. There's other shit thrown in there for good measure, too—the gabber kick-drum squash on "Asia," or the almost-dubstep bass pressure on "Tair"—but pinpointing all those parts implies a reverence for influence that Salem doesn't really bother with. "We're taking liberally from so much," says Donoghue. "We're taking from rock, drone, European rave music, southern rap, Chicago, New York, whatever."

When I mention specific artists like Chicago juke/footwork producer DJ Nate, Donoghue says he's never met the early-20-something beatmaker, but he's definitely a fan. "His music is so smart," he says, "but I don't think he's, like, trying to be clever." Other guys like Gucci Mane (of whom Salem has done several unofficial remixes) and Wacka Flocka Flame are held in similarly high regard, but it's more like a detached appreciation than anything resembling gushing. "We don't really know that much about any one kind of music," says Holland. "We like so many different kinds of music, but we don't do too much background research. We're just trying to find individual songs that we like."

"We all focus on different things, too," Donoghue adds. "Like, I know Heather really likes music that has bells in it—more than I do—and I like certain rap that John and Heather can appreciate, but maybe not listen to it as much. John has a whole bunch of other shit that I don't even know about at all. But we share a lot of music with each other and we share a lot of ideas—verbal and conceptual. Salem is where all our aesthetics meet."

The band works on songs collectively, but each member has a specific identity within each track. On "Trapdoor," Donoghue raps in a pitched-down, incomprehensible growl, and his hook, "It's all blurred out/Hey bitch, I can't see ya" could almost be mistaken for Gucci Mane. On "Traxx," Marlatt's singing is pure texture amidst a haze of deathray synths, bass, and prison clanks. And Holland sings as well. On "Killer," he conjures up a strange, rap-laced industrial rock combination that borders on pure noise.

Salem's influences might seem a little iPod-playlist-driven, but in an era of Rick Ross studio gangsterism and rock 'n' roll dudes coming out with macrobiotic cookbooks, it's hard to harp too hard on authenticity. That said, if M.I.A. can be burned at the stake for eating truffle fries, what does it mean when white kids with art-school credentials start pitching their voices down to sound like Gucci Mane?

"No one would ever question us for, like, reversing a guitar or something," says Donoghue. "And, like, with juke, I'm from Chicago. I grew up in Chicago."

"And I lived there for five years," adds Holland.

"I feel like that's something a white person would say," says Marlatt. "In a way to criticize what we're doing. It's like, to anyone that thinks that in this era—I don't know what to tell them. It's not like we're Elvis Presley. God. What, are we robbing the music from a different race? Give me a break."

"There's no such thing as owning anything in music or art or anything like that," says Holland.

"Yeah, like, I've found music that has been remade from chopped-up parts of beats that I did in high school," says Donoghue. "But I'm happy [someone] took the song in a different direction. It's not anyone's song."

That's the sort of controversy that surrounds Salem these days. That, and grumblings about their live shows, the most ballyhooed of which was at the SXSW FADER Fort earlier this year. According to those who were there, including The FADER magazine's own Matthew Schnipper, the show fell somewhere between brilliantly not good and just not good—they may or may not have been booed off stage, it's hard to tell. At any rate, videos from the performance remain on YouTube.

When I ask Salem about SXSW and the FADER Fort videos, there's a moment of sincere confusion.

"I never, like, saw the video, so I don't know," says Marlatt.

"Was that, like, a YouTube video?" asks Donoghue. "I don't get it."

"Yeah, it's on YouTube," I say. "I guess the video was taken offline for a second or something?"

"That was only, like, our eighth show," Holland says after a long pause.

"There's a lot of people that want to weigh in on our live show and how it is and how it should be," Donoghue says, almost laughing. "I'm just like, straight up, I would never talk to you. I wouldn't talk to you about what I want my music to sound like, I wouldn't talk to you about what I wanted my art to look like, or like, hang out with you. So why do you think you should be weighing in on things?"

"I wanna be like, 'Why didn't you ask someone else to do it then?'" says Marlatt. "People were saying stuff like, 'Other bands would die to have the opportunities that you guys have, to get the shows that you get.' Like, [these bands] trying for years, and then they finally get to play [the FADER Fort]. And I don't even know what to say when people say stuff like that. It's like, 'Okay, well… sorry?'"

"The only reason we started doing shows was because someone offered to fly us to Rome to play," admits Donoghue. "So we were like, 'Okay, that would be fun,' you know what I'm saying? We're still trying to figure it out, and we will figure it out, but live performance isn't really—we don't have that much experience with it. We're still trying to come to a place where it's as moving as the actual music we make. These shows were part of our exploration phase. We're playing bigger venues than maybe we're prepared for."

The problem is, people still really want to see Salem—at least people like music journalists, Terence Koh, and Michael Stipe—all of whom showed up to what was probably Salem's third or fourth show at Brooklyn's Glasslands Gallery in January. How do you keep such heavy-hitters away while Salem slowly, painfully perfects its live show?

"I don't even care. I totally don't," says Marlatt. "I'm totally confused by that whole world. I think we're more concerned with doing performance-based things, rather than standing around... just playing music. We want to do way more than that. But up until this point we haven't had any of the resources to really do what we have in our heads. But now we kind of do, and that's exciting."

As the interview continues, there's a loud noise that keeps barging its way into the phone call—either a large barking dog or maybe a boar—and I'm reminded that Holland and Marlatt are set up in Northern Michigan—home of Midwestern desolation, pain and suffering, upside-down crosses stuck in the snow, etc. But I'm also struck by how laid-back and sort of positive everyone seems to be.

"I feel like people imagine us as being so serious or dark or whatever," says Marlatt, "but it's not really like that. We don't take ourselves seriously, but we take our music very seriously. It's not about each of us as individuals. Like, 'Oh, Jack went to a party last night.' Who cares? It has nothing to do with our music."

Prior to talking with Salem, it all seemed so obvious: Teams of marketing men carefully cultivated this band's persona using magnets and only the best SEO-baiting tricks—some real buzzband conspiracy shit! But it turns out the reality is much more banal. Their music—and their aesthetic aura—is ambiguous and full of fuzzy definitions, but Salem is not part of a JT LeRoy-style hoax; the darkness and the crack smoking and whatever else come from a more intuitive lack of giving a shit than some secret, unfolding plan.

"I think you're giving us more credit for thinking about our 'audience' than we actually do," Donoghue eventually admits. "We're not even trying to be secretive or sensational. It's just that we're not thinking about people passing judgments. We're making what we want to be listening to. It's not like we're making anything just to get a reaction from people. If we just wanted to be sensational or whatever, we have a lot more stories we could have told."

King Night is out September 28 on IAMSOUND